Discussing the statistics and consequences of violence at work and the role of self-defence training in reducing its impact.

Are you concerned about violence in the workplace? You're not alone.

A recent survey found that 12.5% of workers in Europe experienced some form of violence at work [1]. Workplace violence is a global issue and a major concern for employers and employees across most industrialised countries [2, 3].

“Globally, more than one in five persons in employment has experienced violence and harassment at work during their working life” (ILO 2022) [4]

Whilst workplace violence is commonly understood as a sudden act of physical violence, the reality is a much a broader range of situations. The mental and physical health implications for the workforce are significant and lead to poor performance, motivation and staff retention.

As concerns about workplace safety continue to grow, understanding and addressing the causes and consequences of violence at work has become more important than ever.

“Violence has high economic costs – preventing violence can promote economic growth” (WHO 2014) [5]

In this article we will discuss what is workplace violence, its prevalence and consequences for employees and employers. And we will discuss how self-defence training can help avoid or mitigate its impact.

Let’s get to it,

What is workplace violence?

There is no single uniform definition of “workplace violence”. This is due to the fact that the perception of what constitutes “violence” varies among individuals and cultures [6].

In other words, some people mean to harm others but, based on their cultural backgrounds and beliefs, do not perceive their acts as violent [3].

This is illustrated by popular expressions such as the English "tough love", the French "qui aime bien, châtie bien", or the Spanish "quien bien te quiere, te hará llorar" among others.

In a study among staff of a health department in Northern Ireland [7], all respondents regarded physical assaults as violence but:

- only 93% considered threatening behaviour as violence

- only 84% considered verbal abuse as violence

- only 49% considered sexual harassment as violence

- only 40% considered derogatory/antagonistic or discriminatory comments as violence

This variability in the perception of what constitutes violence is a difficulty when studying violence so occupational health researchers make the distinction between two types of violence [8]:

- Mega violence: violence universally recognised as violence

- Micro violence: violence such as incivility that may not be universally recognised as violence

The distinction between Mega violence and Micro violence can provide a useful framework to understand the complex dynamic of violence at work.

Defining violence

For the World Health Organization (WHO) violence is:

“The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation.” (WHO 2002) [3]

It is noteworthy that the definition used by the WHO associates intentionality with the committing of the act itself, irrespective of the outcome it produces, and expands the conventional understanding of violence with the term “power”.

Similarly, the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) defines violence as:

“A generic term that covers all kinds of abuse: behaviour that humiliates, degrades or damages a person’s well-being, value or dignity.” (EU-OSHA) [9]

And in Great Britain, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) sees workplace violence as:

"Any incident in which a person is abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances relating to their work. This can include verbal abuse or threats as well as physical attacks.” (HSE 2006) [10]

It is important to remember that this can include:

- verbal abuse or threats, including face to face, online and via telephone

- physical attacks

Many forms of violence can result in physical, psychological and social problems that do not lead to injury, disability or death [3] so specialists now use the more comprehensive and neutral designation: “adverse social behaviour” [1].

Adverse social behaviour (ASB) can refer to instances of:

- Harassment (bullying, mobbing)

- Physical violence

- Verbal abuse or threats

- Unwanted sexual attention

Types of Workplace Violence

When it comes more specifically to violence at work, occupational health researchers have classified violence into the following 4 types [11]:

- Type 1, Criminal Intent: The perpetrator has no legitimate relationship to the business or its employees, and is usually committing a crime in conjunction with the violence. These crimes can include robbery, shoplifting, and trespassing.

In the US, the vast majority of workplace homicides (85%) fall into this category. - Type 2, Customer/Client: The perpetrator has a legitimate relationship with the business and becomes violent while being served by the business. This category includes customers, clients, patients, students, inmates, and any other group for which the business provides services. It is believed that a large proportion of customer/client incidents occur in the health care industry, in settings such as nursing homes or psychiatric facilities; the victims are often patient caregivers. Police officers, prison staff, flight attendants, and teachers are some other examples of workers who may be exposed to this kind of workplace violence.

- Type 3, Worker-on-Worker: The perpetrator is an employee or past employee of the business who attacks or threatens another employee(s) or past employee(s) in the workplace.

Worker-on-worker fatalities account for approximately 7% of all workplace violence homicides in the US. - Type 4, Personal Relationship: The perpetrator usually does not have a relationship with the business but has a personal relationship with the intended victim. This category includes victims of domestic violence assaulted or threatened while at work.

These categories can be very helpful in the design of strategies to prevent workplace violence, since each type of violence requires a different approach for prevention, and some workplaces may be at higher risk for certain types of violence.

The devil & the details: studying workplace violence

Research on work-related violence dates back to the late 1970’s, but it wasn't until the 1990’s that the issue gained significant attention from the public, health organizations, authorities, and employers alike [12].

Each approach/methodology used to study workplace violence casts a different light on the problem, and, sometimes, the discrepancy between the results of different studies can be quite striking and perplexing.

For example, reported incidence of bullying varies from 5% to 55% depending on the frequency used to qualify the experience as "bullying" ("weekly basis", "occasional", "one or more negative behaviour").

Saying that the methodology is important is an understatement. What exactly is measured is equally important. For example:

- the 2019/2020 Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW 2019/2020) reports that around 1.4% of workers in England and Wales are the victims of one or more “violent incident” at work each year [13].

- the European Working Conditions Survey: 2015 (EWCS 2015) found that 20% of workers in the UK experienced some form of “adverse social behaviour” at work [14].

As usually, the devil’s in the details.

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) which is commissioned by the Home Office and produced jointly with the Health & Safety Executive, only considers “Assaults” and “Threats”.

On the other hand, the EWCS’s “Adverse social behaviour” label encompasses a wider range of antisocial behaviours such as “Verbal abuse”, “Bullying, harassment” and “Unwanted sexual attention”.

So, in a way, these two reports don't mesure the same thing. The EWCS gives a much more comprehensive picture of the larger issue of violence at work than the CSEW whose figures tend to minimize the problem.

“Defining outcomes solely in terms of injury or death thus limits the understanding of the full impact of violence on individuals, communities and society at large”. (WHO 2002) [3]

But the confusion can go deeper.

Whilst the CSEW obviously uses the word "assault" in its ordinary meaning of "a physical attack", it is noteworthy that the terme "Assault" covers a range of actions under the common law.

According to Sentencingcouncil.org, the law in the UK distinguishes three types of assaults:

- Common assault: i.e. threats.

When a person inflicts violence on someone else or makes them think they are going to be attacked. It does not have to involve physical violence. Threatening words or a raised fist is enough for the crime to have been committed provided the victim thinks that they are about to be attacked. Spitting at someone is another example. - Actual bodily harm (ABH): i.e. physical attacks with minor injuries.

When the assault has caused some hurt or injury to the victim. Physical injury does not need to be serious or permanent but must be more than “trifling” or “transient”, which means it must at least cause minor injuries or pain or discomfort. Psychological harm can also be covered by this offence, but this must be more than just fear or anxiety. - Grievous bodily harm (GBH)/wounding: i.e. physical attacks with serious injuries.

When the assault has caused serious physical harm. It does not have to be permanent or dangerous. For example, a broken bone would amount to GBH – in some cases a broken bone might lead to permanent disability but, in others, it might heal without leaving any long-term effects. GBH can also include psychiatric injury or someone passing on an infection, for example through sexual activity.

So we can see here that the CSEW uses "Threats" for "Common assaults", and groups ABH and GBH under the term "Assaults".

Similarly, in the US, some reports or articles might mention "simple assault" and "aggravated assault"[11]. In the American context, the former likely refers to "the wrong act of causing someone to reasonably fear imminent harm" (equivalent to "threat" in the CSEW) while the latter is "an assault that causes serious bodily injury" (equivalent to "assault" in the CSEW).

So, the main takeaway for me it that the definition of a term (i.e. what it exactly means) and the methodology used are crucial to fully understand and address the issue of workplace violence, particularly when comparing or contrasting data from different sources.

Prevalence of workplace violence

According to the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), in Great Britain, acts of violence account for 8% of all non-fatal injuries reported under Reporting of Injuries, Disease and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (RIDDOR) 2020/21 [17].

Under the RIDDOR regulations, British businesses are legally required to report a specified list of workplace injuries which cause the target to be off work for more than three days.

Through its various forms, adverse social behaviour is a widespread phenomenon in the workplace.

A recent survey by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (EWCTS 2021) [14] found that, on average, 12.5% of workers in Europe (i.e. including the UK) experienced some form of adverse social behaviour at work [1].

But there are significant variations at national levels [14]:

Such differences may reflect different levels of cultural awareness of, and sensitivity to, the issue as much as differences in actual incidence.

Additionally, it is important to bear in mind that the various forms of violence often coexist and overlap [4].

Assaults and Threats

The Fourth European Working Condition Surveys (EWCS 2007)[9] found that:

- 5% of workers have been personally subjected to violence

- 6% of workers reported that they have been exposed to threats of physical violence either from fellow workers (1/3) or from others (2/3)

These numbers are consistent with estimates from other industrialised nations such as the USA [16].

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) reports 688,000 incidents of violence at work in 2019/2020: 299,000 were physical assaults (43.5% of violent incidents), 389,000 were threats (56.5% of violent incidents) [13]:

In the US, for the period 1992-96, "threats" represented around 77% of the violent acts in the workplace and "assaults" 33% [11].

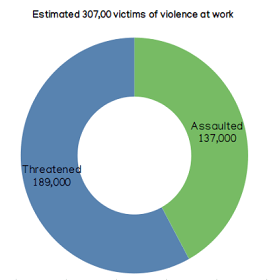

In terms of victims, for the same period, an estimated 307,000 adults were victim of workplace violence: 137,000 were assaulted and 189,000 were threatened [13].

The overall number of victims of violence does not equal the sum of assaults and threats as some victims will have experienced both assaults and threats.

Gendered violence and sexual harassment

The European Working Condition Telephone Survey 2021 (EWCTS 2021), indicates the share of women experiencing some form of adverse social behaviour at work is consistently higher than that of men [1].

In the US, statistics from 2005 on the characteristics of individuals who commit workplace violence show that 80% of them were males over the age of 30 [34].

The gender gap is particularly striking when considering “unwanted sexual attention”:

According to the report, women are 3.6 times more likely to suffer from unwanted sexual attention than men.

What’s more, the likelihood of a young woman (18–34 years) reporting unwanted sexual attention is three times higher than men of the same age, and 10 times higher than the oldest group of men (50+ years) [1].

In the UK, a 2017 BBC live survey found that 53% of women (and 20% of men) had experienced sexual harassment in the workplace [19]. This ranged from inappropriate comments to actual sexual assaults.

The BBC survey followed the publication of a major report on sexual harassment in the workplace by the Trade Union Congress (TUC) and the Everyday Sexism Project [18]. It was found that:

- 55% of all women polled have experienced some form of sexual harassment

- 35% of women have heard comments of a sexual nature being made about other women in the workplace

- 32% of women have been subject to unwelcome jokes of a sexual nature

- 28% of women have been subject to comments of a sexual nature about their body or clothes

- 25% of women have experienced unwanted touching (such as a hand on the knee)

- 20% of women have experienced unwanted sexual advances

- 10% of women reported experiencing unwanted sexual touching or attempts to kiss them

- 80% of women did not report the sexual harassment to their employer

In the vast majority of cases, the offender was a male colleague. Nearly one in five victims reporting that their direct manager (or someone else with direct authority over them) was the perpetrator [18].

Whilst sexual harassment most commonly consists of “repeated unwelcome, unreciprocated and imposed” actions, it is noteworthy that a single incident can be called “sexual harassment”. This is why the term unwanted sexual attention is preferred.

Sexual harassment in the workplace is such an acute issue that in 2017 the House of Commons commissioned a special report on the matter.

Their conclusion was unequivocal:

“Sexual harassment in the workplace is widespread and commonplace. It is shameful that unwanted sexual behaviours such as sexual comments, touching, groping and assault are seen as an everyday occurrence and part of the culture in workplaces.” (HoC 2018) [20]

Overall, research shows that unwanted sexual attention is

“disproportionately perpetrated by men and disproportionately affecting women”.

As we’ll discuss more in details later, the financial cost of sexual harassment for the employers and society in general is shocking.

Harassment / bullying / mobbing

Harassment (aka bullying, mobbing) involves:

- repeated negative, aggressive or hostile acts

- a possible variety of negative or hostile acts

- the victim having difficulty in defending him/herself

According to various studies [9], the essential features of harassment are:

- its escalating nature: the victim can do very little to solve the situation and the methods become increasingly serious with time

- the personalisation of the conflict: as time goes on the target becomes stigmatised — he/she becomes “the problem”

- the collective nature of the process (i.e. perpetrators gang up against the victim)

As is often the case with human behaviour, harassment follows patterns. The stereotypical course of bullying has been described as a four-stage process [21]:

- Critical incident: the situation begins with a conflict that triggers a critical incident

- Bullying and stigmatising: the second stage comprises different negative acts and harassment

- Personnel management: personnel-administrative actions start

- Expulsion: in the fourth stage the target/victim is displaced from the workplace

In the United Kingdom, 1.4 % of respondents from 70 organisations within the private, public and voluntary sectors report being bullied at work at least weekly, and 10.6 % being bullied less frequently than weekly [22].

Studies reveal a wide variation in the prevalence of bullying dependent upon the occupation or sector involved [32].

Relationship between offender and victim

The relationship between offender and victim is an interesting aspect of workplace violence.

In Great Britain, it is estimated that 60% of aggressors were strangers to the victims but 40% were known to the victims, with colleagues representing 3% of the cases [13].

In cases where the offender was known, they were most likely to be a client/member of the public known through work.

Occupations most at risk of workplace violence

Research by the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) brought to light that the risk of third-party violence (i.e. from strangers, customers, patients, etc.) is substantially higher in some occupational sectors [9]:

- healthcare and social work

- education

- commerce

- transport

- public administration

- security and defence

- hospitality

In the UK, the 2020 Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) reached similar conclusions [13].

The most at risk occupations are, in descending order:

- protective service occupations (i.e. security staff, police officers, etc)

- health and social care professionals (i.e. doctors, nurses, paramedics, etc)

- managers

- sales and retail occupations

- teaching and educational professionals

- skilled agriculture and related trades

- transport and mobile machine driver

Interestingly, the figures indicate that whilst protective service occupations are most at risk of assault, social care professionals and sales occupations are more at risk of threats [12].

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) is a study of the employment circumstances of the UK population.

The 2020 survey shows that around 9 out of every 10 workers who sustain an injury resulting from violence at work are employed in public services [13]. This includes human health and social work activities, education and public administration and defence.

Violence at work in the Health and Social Care sector

In Europe [1,9] like in the USA [15], Health and Social Care is one of the industries where staff is the most exposed to violence.

The EWCTS 2021 suggests that Healthcare services workers are 2–3 times more likely to report bullying, harassment and violence [1].

In the UK, the latest NHS Staff Survey (2021) indicates that 16.6% the staff has experienced physical violence at least once in the past year, and 57.8% has experienced harassment, bullying or abuse [23]

The situation is so appalling that, in 2020, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care had to address the issue in a correspondence. Among other things, he mentioned that 34% of ambulance trust staff had experienced physical violence from members of the public and patients [24]. The figure was 31% in 2014 [25].

A previous 2004 study which examined aggression towards health care staff in a UK general hospital, had the following figures (% of respondents / within the preceding year) [26]:

- 68.3% verbal aggression

- 23.2% threats

- 26.9% physical aggression

More granular figures for physical aggression show that some health workers are more likely to face violence:

By departments:

Percentage of staff that was physically assaulted:

- over 42% of the medical department staff

- 36% of the surgical staff

- over 30% of the A&E staff

By profession:

Staff nurses and enrolled nurses reported the most assaults (43.4%) and doctors, the fewest (13.8%).

Violence at work in the Retail sector

The EWCTS 2021 reveals that people who deal with customers (i.e. front-line workers) are twice as likely to experience adverse social behaviour at work compared to those who don’t [1].

So, unsurprisingly, the situation in sales and retail occupations is bad.

The British Retail Consortium (BRC) Crime Survey 2022 reports 1301 violent or abusive incidents everyday [27]. This is about 400,000 incidents per year.

Of these 1301 daily incidents:

- 21 violence with injury

- 104 violence without injury

- 1176 abuse

Overall, 15% of the workforce in the retail industry suffered some kind of harassment at work. And 70% of retailers see violence as the number one threat [27].

The problem of violence is particularly acute for front-line workers. The EWCTS 2021 reveals that some front-line workers reported verbal abuse or threats as much as 2.5 times the EU average [1].

Violence at work in the Hospitality sector

Adverse social behaviour is a particular problem in the hospitality sector where long hours, high social contact, large crowds and alcohol all create a difficult working environment.

We covered this issue in details in another article (Workplace violence in the hospitality industry) so I’ll just give a brief summary here.

Various studies have shown that a high proportion of pub licensees in the UK experience violence [28, 29, 30].

The situation is so bad that a number of local authorities have added supplementary personal safety measures criteria to their licensing policies.

Violence at work in the Education sector

The 2019-20 Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) shows that teaching and education professionals have the sixth highest level of violence at work, out of 25 occupational areas [13].

A survey by the National Association of Schoolmasters/Union of Women Teachers (NASUWT) in April 2021 found that [31]:

- 6% of the teachers surveyed by the union said they had been subjected to physical violence by pupils in the past year

- 10% said they had received threats of physical violence from students

- 38% said they had been subjected to verbal abuse from student

Overall, the level of violence against educators is alarmingly high (higher than customer service).

Key factors of workplace violence

Risk factors for work-related violence is another important line of research.

Various international studies have found special features of work and work environment that increase the risk of violent assault at work [9]:

- the handling of money or valuables (cashiers, transport workers, bank and post office staff, shop assistants)

- guarding valuable property or objects

- dealing with the public

- providing care, advice, education and training (nurses, ambulance staff, social workers, teachers)

- working in a social function

- carrying out inspection or enforcement duties (police and traffic wardens, ticket inspectors)

- working with the mentally disturbed, drunk or potentially violent people (prison officers, bar staff, mental health workers)

- working alone (home visitors, taxi drivers, domestic workers, small shops, cleaning, maintenance and repair)

- working in a mobile workplace

- working at night or early in the morning

- working in a crime black spot

In the UK, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) highlight the following key factors of workplace violence [13]:

- working in locations where there is a known high risk of violence

- late evening or early morning work, when fewer workers are around

- lone workers, such as security staff, who have authority over customers and are enforcing rules

- people affected by alcohol or drugs

- carrying money or valuable equipment

The issue of lone workers deserved an article in itself and has been covered elsewhere (How many lone workers are attacked every day in the UK?).

According to research by the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA), risks factors for third-party violence emerge mainly from features of the work environment but also from a wider context as well as particular situations.

Some individual characteristics such as gender (male), age (young), work experience (little) seem also to be connected with higher risk for third-party violence [9].

But overall, targets of bullying are as diverse as people in general and there is no common target profile in terms of personality.

In other words, anyone can become a victim; there are no features that are always a risk.

As a summary of the causes of harassment, it has been suggested that, in most of the cases of bullying, at least three or four of the following can be found:

- problems in work design (e.g. role conflicts)

- incompetent management and leadership

- a socially exposed position of the target

- negative or hostile social climate

- a culture that permits or rewards harassment in an organisation

The impact of workplace violence on employees

Some of the impacts of violence are easy to see; others are can be much harder to see.

“The human cost in grief and pain, of course, cannot be calculated.” (WHO 2002) [3]

Workplace violence can have both physical and emotional consequences for victims [32, 33]. Research has also shown that the psychological impact extend to the co-workers and the families of the victims [34].

Physical consequences of workplace violence

Whilst interpersonal violence was not the cause of any of the 123 deaths that occurred in work-related accidents in 2021/22 in the UK, it caused many injuries [9].

To put things in perspective, of the 5,190 fatal workplace injuries that occurred in the United States in 2021, 718 (13%) were cases of violence by another person (CFOI 2021) [35].

Of the 299,000 assaults reported by Crime Survey for England and Wales 2019/20 (CSEW), 38% resulted in physical injuries [13].

Most injuries resulting from assaults are considered minor but 12% are more severe.

* "Other injuries" includes puncture/stab wounds, broken bones, nose bleeds, broken nose, broken, lost or chipped teeth, dislocation, concussion or loss of consciousness, internal injuries, facial or head injuries or other injuries.

Figures may add to more than 100 as more than one type of physical injury may have been sustained.

Physical injuries, however, are only the visible part of workplace violence.

Psychological consequences of workplace violence

The more insidious aspect of workplace violence is its impact on mental health, cognitive capacities, and social relations.

In the aftermath of a violent event, the universal concern among the victims, their families and their co-workers is “recurrence” [36, 37].

The consequence is that employees no longer see their workplace as safe [33]. This in turn leads to anxiety and various forms of mental health issues [33].

“The unique impact of interpersonal trauma [...] compared with noninterpersonal trauma, is the experience of an environment as unsafe and unpredictable, due to the potential of human threat.” (Forbes et al. 2014) [38]

A large body of research also confirms that direct and indirect exposure to violence results in serious psychological effects such as depressive symptoms [39], post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (i.e. distressing emotions, difficulty thinking, withdrawal, etc.) which in turn can lead to absenteism and job change [40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46]

One study, in particular showed that it was not unusual among hospital staff to experience anxiety after being threatened or assaulted [43].

The prevalence of PTSD symptoms during the 7 days after the violent event was significant:

- 17% had score high enough to be diagnosed with PTSD

- 15% had scores associated with suppressed immune system functioning

Reactions to violent incidents have been categorized as follow [47, 48]:

- short-term emotional: feelings of anger, helplessness

- social: in relation to co-workers, perpetrator

- bio-physiological: sleep-pattern disturbance, body tension

- cognitive reactions: compulsive thoughts about the incident, anger towards authority

- long-term emotional: fear

Other studies have looked at the issue in terms of direct and indirect outcomes of workplace violence [49]:

Direct outcomes:

- Negative mood

- cognitive distraction

- fear of violence

Indirect outcomes:

- psychological (e.g. depression)

- psychosomatic (e.g. headaches)

- organisational (e.g. absenteeism, presenteism, turnover intentions, emotional exhaustion, accidents, impaired performance)

All these outcomes have an important impact on organisations.

The impact of workplace violence on organisations

Whilst victims bear the emotional and physical costs, violence at work has deep and negative impact on organisations too.

The consequences of workplace violence to organisations comes in various forms such as [50]:

- Sickness absenteeism

- Replacement costs incurred by employee turnover

- Reduced productivity/performance

- Knock on effects on witnesses or observers of bullying

- Premature or ill-health retirement

- Grievance and complaints

- Litigation and compensation

- Organisational interventions

- Presenteeism

- Brand image and public goodwill

- Corruption, fraud, sabotage and theft

- Impact on quality of products and services

The disruption caused by violence in the workplace

At the level of the workplace, violence causes immediate – and often long-term – disruption to interpersonal relationships, the organisation of work, productivity and the overall working environment [32].

The 2016 TUC report on sexual harassment in the workplace [18], clearly highlighted the wide-ranging impact of unwanted sexual attention:

At minima, adverse social behaviours instil a negative mood in the workforce [33]. This in turn is likely to reduce job satisfaction [51]. The lower the job satisfaction, the lower the job performance [52, 53] and the higher the staff turnover [54, 55].

Further evidence shows that workplace violence leads to [9, 20, 49, 54, 55]:

- increased sickness absenteeism

- higher turnover rates

- reduced job satisfaction

- fall in productivity

- increased insurance premiums

In particular, there is a strong relationship between exposure to violence and absenteeism [9, 57, 58]:

The association between workplace violence and symptoms of burnout among health and social care workers is well documented [56, 59, 60].

A recent study highlighted the negative cycle triggered by violence [61]:

- violence causes stress

- stress leads to a perception of decreased safety causing more stress in a negatively reinforcing loop

- stress overload leads to burnout

- burnout leads to a decreased perception of colleague/management support which leads to more burnout in a negatively reinforcing loop

In a 2006 survey by the Anxiety Disorders Association of America (ADAA), a large number of employees reported that stress and anxiety negatively impacted various aspects of their work [62].

Whilst the spectrum of consequences of physical and non-physical violence is large [63], a 2011 study of the impact of violence among Emergency Department (ED) nurses demonstrated that exposure to violence (threats or assaults) was significantly related to decreased productivity in the areas of Cognitive Demands (i.e. thinking, concentrating, etc.) and Support/Communication Demands [64].

In other words, ED nurses who had experienced a violent event were struggling to remain cognitively and emotionally focused and had trouble communicating with their colleagues.

It is noteworthy that coworker-initiated aggression and public-initiated aggression tend to have different impacts [65]:

- Coworker-initiated aggression negatively affected emotional well-being, psychosomatic well-being, and organisational aspects

- Public-initiated aggression affected perception of likelihood of future violence and directly predicted employee intent to turnover

At the end of the day, all this organisational disruption has a negative economic impact. At the very least, employers bear the direct cost of lost work time and funding for improved security measures [31].

Estimated Economic Cost

Various studies found that in the early 1990ies, assaults and murders at work cost the US economy over USD4.2 billions [32] and that up to half a million employees miss a total of 1.8 million days of work each year because of violence at work [66].

In 2000, the British Crime Survey estimated that 3.3 million work hours were lost each year in the UK due to workplace violence [67].

"[…] existing evidence attests to the substantial cost of psychosocial workplace aggression […] albeit such derived estimates are likely gross underestimates" (Hassard et al. 2017) [68]

The “bottom line” being the main influence on management decisions, trying to quantify the financial cost of adverse social behaviours has been a centre of interest for academics, unions and various organisations.

A large part of the cost of adverse social behaviour is indirect such as absenteeism, staff turnover and productivity loss.

Taking this into account, a 2008 research commissioned by the Dignity at Work Partnership (a partnership project funded jointly by Unite the Union and the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform) estimated that the cost of bullying to companies in the UK amounted to £13.75 billion for the year 2007 [50]:

A recent review revealed that whilst the annual cost of psychosocial aggression varied from country to country, it remains staggering [68]. This review looked at at studies from five different national contexts across the US, Europe and Australia, that focused on estimating the cost of workplace-violence.

Australia

- estimated total cost of workplace bullying per year: between USD5.7 and USD35.1 billion

- cost per working-aged adult: between USD460.06 to USD2,830.55

- cost estimate of workplace bullying-related depression annually: USD310.1 million

United Kingdom

- total cost of workplace bullying: USD23.4 billion annually.

United States

- cost of abusive supervision: USD31.7 billion annually

- mistreatment-related absence: USD4.4 billion annually

The burden of violence is particularly heavy for the healthcare sector, so estimating its cost has been the focus of various studies. A recent one which looked at the annual cost of bullying and harassment to NHS England, reached the conclusion that mobbing cost the institution a total of £2.281 billion per annum [69].

Across these studies, the largest cost components were:

- presenteeism (between 70% and 80%)

- sickness absence (10% to 18%)

- turnover (5% to 12%)

In 2019, Deloitte Access Economics published a report on the economic costs of sexual harassment at work [70]. It was found that in 2018 workplace sexual harassment alone cost Australian employers AUD1.974 billion (approx. USD1.3 billion):

- AUD1,840.1 million in lost productivity (absenteeism, presenteeism, job turnover, manager time)

- AUD134.3 million in other costs (compensation for victims, legal fees, healthcare, etc.)

It is noteworthy that the overall cost of sexual harassment for the Australian society as a whole (i.e. employer + employee + state) was estimated at AUD3.808 billion (approx. USD2.5 billion) in 2018.

Considering that the UK workforce is 2.6 times bigger than the Australian workforce, we could speculate that the annual cost of sexual harassment for UK employers is somewhere around USD3.4 billion (approx. £2.8 billion).

More recently, the 2022 BRC Crime Survey found that in the UK the overall cost of violence for the retail sector alone was £1.5 billion [27]:

- £786 millions: losses from actual incidents

- £715 millions: cost of crime prevention

The economic consequences of workplace violence on organisations are colossal and would justify viewing Health & Safety as an integral part of good business practice, but

“unless the financial reporting system for an organization directly attributes costs against causes, the true expense for an organization is unlikely to ever be revealed” (Chappell & Di Martino 2006) [32]

The role of self-defence training in reducing violence at work

As we’ve seen, the term “workplace violence” covers a wide range of behaviours (best labelled adverse social behaviours) ranging from harassment (aka bullying, mobbing) and verbal abuse or threats to physical violence and unwanted sexual attention.

“A growing number of scientific studies demonstrate the preventability of violence.” (WHO 2014) [5]

At first sight, it would seem that corporate self-defence training only addresses the cases of physical/sexual assaults. After all, self-defence training is about providing employees with the ability to avoid injuries and escape danger.

A comprehensive self-defence programme, however, will do a lot more than that.

With a good holistic approach, it will be able to cover the full spectrum of adverse social behaviours. It will also include measures to prevent and mitigate workplace violence and offer adequate solutions to help organisations tackle the general issue.

Here is how...

Raising awareness

Raising awareness is crucial in tackling societal issues. It helps to inform and educate people, promote understanding and empathy, and encourage action towards finding solutions and generating change.

A good self-defence training programme will help your organisation achieve all of these points:

- Increasing understanding: providing people with relevant facts, statistics, and information that they may not have been aware of will help them to gain a better understanding of the issue of adverse social behaviours. This increased understanding helps to break down stereotypes and stigmas, and promotes empathy and compassion.

Particularly, many people might not be aware there are the victims of toxic, unacceptable, behaviours.

Similarly, perpetrators can be insiders (colleagues) who reproduce learnt behaviours without necessarily realising the impact they have on people around them. Raising awareness can help people change. - Encouraging action: when people become aware of an issue, they are more likely to take steps to address it. Additionally, a good self-defence programme will empower people to take action and avoid the “bystander” effect. This in turn will lead to increased engagement, involvement, and support for the cause

- Sparking dialogue: raising awareness helps to create a dialogue about the issue. More dialogue lead to a better understanding of the root causes, as well as potential solutions. A fun, engaging self-defence workshop can be the perfect setting to break down barriers, starts a conversation and foster initiatives and collaborations.

Self-defence training can also help build teamwork and camaraderie among employees. When employees participate in training together, they develop a stronger bond and sense of trust, which can lead to a more cohesive and effective team.

Sending a strong message

Violence or harassment often leave the victims and their co-workers, feeling helpless. Allowing inappropriate behaviour to go unchecked will result in the workforce feeling uncomfortable and potentially at risk with all the consequences we’ve seen in previous sections.

“Despite the fact that violence has always been present, the world does not have to accept it as an inevitable part of the human condition.” (WHO 2002) [3]

As part of an organisation’s effort to tackle the issue of workplace violence, a self-defence course can send a strong message:

- To the staff in general, it says “we care and we’re taking the issue of your well-being and safety seriously”.

- To the victims, it says “you’re not alone and we’re supporting you”.

- To the perpetrators, it says “these behaviours are not acceptable, we’re taking the issue seriously and we’re not bluffing”.

A self-defence course is a very concrete step that can be implemented well before any incident actually occurs.

Teaching people to assert their boundaries

One of the main elements to counter harassment and bullying, is the notion of boundaries.

This is particularly crucial in cases of sexual harassment as studies have shown that forceful resistance is the safest and most efficient strategy to thwart sexual assault. And the first step in forceful resistance is asserting one’s boundaries.

Self-defence training teaches people how to confidently establish their boundaries in the physical space as well as in the mental space.

When a conflict arises in the workplace, it is always better to address the issue early on while emotions are still under control. Being able to calmly and confidently tell a bully to “back off”, for example, is a powerful way to assert one’s boundaries and stop a situation before it escalates.

Physically, "asserting boundaries" means keeping control of your personal space. This is key when confronted with violence or potentially dangerous situations.

Teaching people to recognise patterns of violent behaviour

Teaching people to recognize patterns of violent behaviour is essential in self-defence. It can help them to identify potential threats and avoid dangerous situations.

For example, a person who understands the warning signs of an impending attack may be able to identify when someone is acting aggressively or displaying body language that suggests they are about to become violent.

This awareness will enable them to better assess the intentions of others and to make informed decisions (de-escalate or avoid) about how to respond to potential threats.

Increasing safety & confidence / Reducing anxiety and stress

“Increased safety”, “increased confidence”, “reduced fear and anxiety”, “reduced stress” are common tropes in the self-defence industry.

It is true, however, that by providing employees with the tools they need to protect themselves (including conflict resolution and interpersonal communication) and to escape violent situations, a self-defence course will help individuals to develop greater confidence in their abilities and enable them to react more effectively to conflictual situations. This in turn will help to reduce fear, anxiety and stress.

Overall, a comprehensive self-defence program that addresses physical, mental, and emotional aspects of workplace violence is essential for creating a safe and respectful workplace culture.

Want to Learn more about Workplace Violence & Safety

Read some of our articles

References

1. Ivaskaite-Tamosiune, V. and Parent-Thirion, A. (2023) Violence in the workplace: Women and frontline workers face higher risks. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Permalink: https://eurofound.link/ef23039

2. ILO (1998) Violence on the job—a global problem. International Labour Organization. Retrieved March 2023, from https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_007970/lang--en/index.htm

3. WHO (2002) World report on violence and health. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland

4. ILO (2022) Experiences of violence and harassment at work: A global first survey. International Labour Organization and Lloyd’s Register Foundation. Geneva: ISBN 9789220384923 (web PDF). https://doi.org/10.54394/IOAX8567.

5. WHO (2014) Global Status Report On Violence Prevention. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland.

6. Walters RH, Parke RD. (1964) Social motivation, dependency, and susceptibility to social influence. In: Berkowitz L, ed. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 1.: 231–276. New York, NY, Academic Press. DOI:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60053-2

7. Harvey, H., Fleming, P., and Mooney, D. (2002) Violence at work: an initial needs assessment for the environmental health department as a health promoting workplace. The Chartered Institute of Environmental Health. Retrieved Feb 2023: http://www.cieh.org/JEHR/violence_at_work.html.

8. Privitera, M., Bowie, V. & Bowen, B. (2015) Translational Models of Workplace Violence in Health Care. Violence and Victims, Volume 30, Number 2, 2015.

9. Milczarek, M. (2010) Workplace Violence and Harassment: a European Picture. European Risk Observation Report. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2010. DOI:10.2802/12198 https://osha.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-03/violence-harassment-report.pdf

10. HSE (2006) Violence at work. A guide for employers. Health and Safety Executive INDG69. Rev 04/06. Retrieved Oct 2022: https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg69.pdf

11. IPRC (2001) Workplace violence: a report to the nation. Injury Prevention Center Research (IPCR). The University of Iowa.

12. SHRM (2019) Workplace Violence: a growing threat, or growing awareness? Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). Retrieved Feb 2023: https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/research-and-surveys/Documents/SHRM%20Workplace%20Violence%202019.pdf

13. HSE (2020) Violence at Work statistics, 2020. Health and Safety Executive. Retrieved Oct 2022: https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causinj/violence/work-related-violence-report.pdf.

14. Eurofound (2015) Sixth European Working Conditions Survey: 2015 (EWCS 2015). European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound). Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. Retrieved Feb 2023: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/european-working-conditions-surveys/sixth-european-working-conditions-survey-2015

15. Eurofound (2021) European Working Condition Telephone Survey 2021 (EWCTS 2021). European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound). Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. Retrieved Feb 2023: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/2021/european-working-conditions-telephone-survey-2021

16. Iennaco J, Dixon J, Whittemore R, Bowers L. (2013) Measurement and monitoring of health care worker aggression exposure. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2013;18:3.

17. HSE (2021) Kind of accident statistics in Great Britain, 2021. Data up to March 2021. Annual statistics. Published 16th December 2021. Retrieved Oct 2022: https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causinj/kinds-of-accident.pdf

18. TUC (2016) Still just a bit of banter? Sexual harassment in the workplace in 2016. Trades Union Congress & Every Sexism Project. Retrieved Feb 2023: https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/SexualHarassmentreport2016.pdf

19. BBC (2017) Half of women' sexually harassed at work, says BBC survey. BBC News. Retrieved Feb 2023: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-41741615

20. HC (2018) Sexual harassment in the workplace Fifth Report of Session 2017–19. Women and Equalities Committee. House of Commons. HC 725.

21. Leymann, H. (1996) The content and development of mobbing at work. Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 5(2), pp. 165–184.

22. Hoel, H., Sparks, K., and Cooper, C. L., (2001) The cost of violence/stress at work and the benefits of a violence/stress-free environment, report Commissioned by the International Labour Organisation, (ILO) Geneva, University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology.

23. NHS (2021) NHS Staff Survey 2021: National results briefing. National Health Service. Retrieved Feb 2023: https://www.nhsstaffsurveys.com/static/1f3ea5c952df62a98b90afcf3daa29ac/ST21-National-briefing.pdf

24. GOV.UK (2020) Correspondence Violence against NHS staff: letter to the workforce. Published 18 February 2020. Department of Health & Social Care. Retrieved Feb 2023: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/violence-against-nhs-staff-letter-to-the-workforce/violence-against-nhs-staff-letter-to-the-workforce

25. NICE (2015) Violence and Aggression Short-term management in mental health, health and community settings. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health & National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists.

26. Winstanley, S., & Whittington, R. (2004). Aggression towards health care staff in a UK general hospital: Variation among professions and departments. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13, 3-10. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00807.x

27. BRC (2022) Crime Survey 2022 Report. British Retail Consortium. Retrieved Oct 2022: https://brc.org.uk/media/679978/crime-survey-final-report.pdf

28. Scott, B. (1998) Workplace violence in the UK hospitality industry: impacts and recommendations. Progress in Tourism and Hospitality Research 4:337-347.

29. Blagg H. (2018) Not on the menu. Unite survey, unitelive.org. Retrieved Feb 2023: https://unitelive.org/14506-2/

30. Leather, P., Lawrence, C., Beale, D., and Cox, T. (1998) Exposure to occupational violence and the buffering effects of intra-organisational support. Work and Stress, 12, pp. 161–178.

31. NEU (2022) Violence in schools. National Education Union. Retrieved Feb 2023: https://neu.org.uk/advice/violence-schools

32. Chappell, D., and Di Martino, V. (2006) Violence at Work. International Labour Office, Geneva.

33. Mayhew, C. & Chappell, D. (2007) Workplace violence: An overview of patterns of risk and the emotional/stress consequences on targets. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, Volume 30, Issues 4–5, July–October 2007, Pages 327-33. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.06.006

34. Paludi, M., Nydegger, R. and Paludi, C. (2006) Understanding workplace violence. A Guide for Managers and Employees. Praeger, Westport: Connecticut.

35. CFOI (2021) Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries Summary, 2021. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. USDL-22-2309. Retrieved Feb 2023: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cfoi.nr0.htm

36. Gray, C. (1998) Reducing the Risk of Workplace Violence. Foundry Management and Technology 126 (1998): 74.

37. Upson, A., (2004) Violence at work: findings from the 2002/2003 British Crime Survey,

38. Forbes, D., Lockwood, E., Phelps, A., Wade, D., Creamer, M., Bryant, R.A., McFarlane, A., Silove, D., Rees S., Chapman C., Slade T., Mills K., Teesson M., O'Donnell M. (2014) Trauma at the hands of another: distinguishing PTSD patterns following intimate and nonintimate interpersonal and noninterpersonal trauma in a nationally representative sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014 Feb;75(2):147-53. DOI: 10.4088/JCP.13m08374.

39. Wang, M.; Wang, H.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Y.; & Sun, L. (2022) Association between Workplace Violence and Depressive Symptoms among Primary Healthcare Professionals in Shandong, China: Meaning in Life as a Moderator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 19, 15184. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph192215184

40. McCann, I.L., & Pearlman, L.A. (1990) Psychological trauma and the child survivor: Theory, therapy, and transformation. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

41. McCann, I.L., & Pearlman, L.A. (1992) Constructivist self-development theory: A theoretical framework for assessing and treating traumatized college students. Journal of American College Health, 40(4), 189-196.

42. Herman, J. (1992) Trauma and recovery. New York: Basic Books.

43. Figley, C.R. (1995) Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

44. Laposa, J.M., & Alden, L.E. (2003) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the emergency room: Exploration of a cognitive model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(1), 49-65.

45. Laposa, J.M., Alden, L.E., & Fullerton, L.M. (2003) Work stress and posttraumatic stress disorder in ED nurses/personnel. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 29(1), 23-28.

46. Hilton, N. Z., Addison, S., Ham, E., Rodrigues, N. C., & Seto, M. C. (2022) Workplace violence and risk factors for PTSD among psychiatric nurses: Systematic review and directions for future research and practice. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 29, 186– 203. DOI: 10.1111/jpm.12781

47. Ryan, J. A., & Poster, E. C. (1989) The assaulted nurse: short-term and long-term responses. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 3 (6), pp. 323–331.

48. Lanza, M. L., (1992) Nurses as patient assault victims: an update, synthesis and recommendations. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 6 (3), pp. 163–171.

49. Barling, J. (1996) The prediction, experience and consequences of workplace violence. In VandenBos, G. B., and Bulatao, E. Q. (eds), Violence on the job: Identifying risks and developing solutions. Washington DC, American Psychological Association.

50. Giga, S., Hoel, H. and Lewis, D. (2008) The Costs of Workplace Bullying. Research Commissioned by the Dignity at Work Partnership: A Partnership Project Funded Jointly by Unite the Union and the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform.

51. Barling, J., Rogers, A. and Kelloway, E. (2001) Behind Closed Doors: In-Home Workers’ Experience of Sexual Harassment and Workplace Violence. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 6 (2001): 225–269.

52. Griffith, R. W., Hom, P. and Gaertner, S. (2000) A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents and Correlates of Employee Turnover: Update, Moderator Tests and Research Implications for the Next Millennium. Journal of Management 26 (2000):463–488.

53. Hoel, H. and Cooper, C.L. (2000) Destructive Conflict and Bullying at Work. Unpublished report, University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST), November 2000.

54. Di Martino, V., Hoel, H. and Cooper C. (2003) Preventing violence and harassment in the workplace. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

55. Lapierre, L., Spector, P. and Leck, J. (2005) Sexual Versus Non-Sexual Workplace Aggression and Victims’ Overall Job Satisfaction: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Health Psychology 10 (2005): 155–169.

56. Laeeque, S.H, Bilal, A., Babar, S., Khan, Z., Ul, R.S. (2017) How patient-perpetrated workplace violence leads to turnover intention among nurses: the mediating mechanism of occupational stress and burnout. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2017;27:96–118.

57. Paoli, P. (2000) Violence at work in the European Union: recent findings. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

58. Eurofound (2007) Fourth European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS 2005). European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Luxembourg. Retrieved Feb 2023: http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/ewco/surveys/ewcs2005/index.htm.

59. Vrablik MC, Chipman AK, Rosenman ED, et al. (2019) Identification of processes that mediate the impact of workplace violence on emergency department healthcare workers in the USA: results from a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031781.

60. Disney, L. & Purser, G. (2022) Examining the Relationship between Workplace Safety and Professional Burnout among U.S. Social Workers, Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 19:6, 627-639, DOI: 10.1080/26408066.2022.2090880

61. Wong, A., Sabounchi, N., Roncallo, H., Ray, J., and Heckmann, R. (2022) A qualitative system dynamics model for effects of workplace violence and clinician burnout on agitation management in the emergency department. Health Services Research (2022) 22:75. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-022-07472-x

62. ADAA (2006 ) Stress & Anxiety Disorders Survey. Anxiety Disorders Association of America (ADAA). Retrieved Feb 2023: https://adaa.org/workplace-stress-anxiety-disorders-survey

63. Gerberich, S., Church, T., McGovern, P., Hansen, H., Nachreiner, N., Geisser M., Ryan, A., Mongin, S. and Wat, G. (2004) An epidemiological study of the magnitude and consequences of work related violence: the Minnesota Nurses’ Study. Occup Environ Med 2004;61:495–503. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.007294

64. Gates, D., Gillespie, G. & Succop, P. (2011) Abuse against nurses and its impact on stress and productivity. Nursing economics. 29. 59-66, quiz 67.

65. LeBlanc, M. & Kelloway, K. (2002) Predictors and Outcomes of Workplace Violence and Aggression. Journal of Applied Psychology: Vol. 87, No. 3, 444 – 453. The American Psychological Association. DOI: 10.1037//0021-9010.87.3.444.

66. Harris, T. (1993) Applied Organizational Communications: Perspectives, Principles and Pragmatics. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

67. Budd, T. (2001) Violence at Work: New Findings from the 2000 British Crime Survey, Home Office Occasional Paper, Home Office, UK Government, London, 2001.

68. Hassard, J., Teoh, K., Visockaite, G., Dewe, P., and Cox, T. (2017) The Financial Burden of Workplace Aggression: A Systematic Review of Cost-of-Illness Studies. An International Journal of Work, Health & Organisations, Vol. 32.1: 6-32. DOI: 10.1080/02678373.2017.1380726

69. Kline, R. & Lewis, D. (2019) The price of fear: Estimating the financial cost of bullying and harassment to the NHS in England, Public Money & Management, 39:3, 166-174, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2018.1535044

70. Deloitte (2019) The economic costs of sexual harassment in the workplace. Final report March 2019. Deloitte Access Economics.